New Ways of Tracking How the Daily Indicators Inform the Bigger Economic Picture

… All but unanimously confirming a picture of strong growth

Key Points:

Three separate Federal Reserve ‘nowcasts’ and models call for 6%+ growth in both the first quarter and the whole year

Explaining how exports and imports matter some in the macroeconomic picture (and how unemployment claims and inventories do not)

Producer Price Index and up-close anecdotes show inflation is happening—it’s not just a prediction

A p.s. about the IMF’s rosy view of the global and U.S. economy, and another about consumer credit

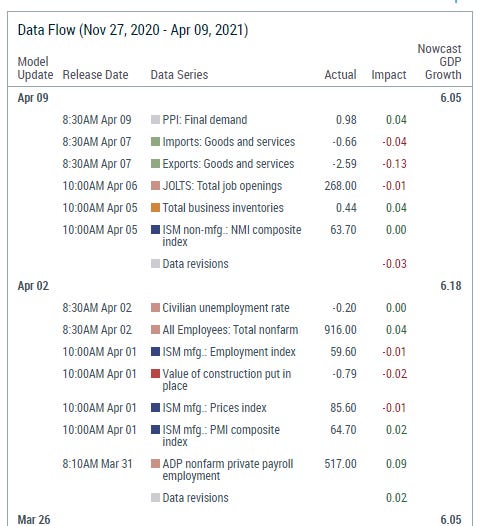

Last week's newsletter never got around to one of my favorite ways of seeing the big picture of our current economic status. That is the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta's 'nowcast' that they call GDPNow. When, two weeks ago, I last checked in with this way of tracking the evolving view of gross domestic product in the first quarter (which as ended, but for which the first official estimate is not released until April 29), the trend had been for downward revisions. In fact that trend generated my headline of two weeks ago about how "First-Quarter Activity Came Down to Earth." From a nowcast of above 9% annual rate of growth, it looked two weeks ago like 4.7% was in the cards. In three updates since then, the estimate has bounced back to 6.0 - 6.2%, and specifically to 6.0% in the last reading on Friday April 9.

These estimators' brethren at the New York Fed have a different 'nowcast' tool that uses really very different inputs and arrives at a different output. At least, it often arrives at a different output. When I checked back in the early winter, I saw that this tool—known as New York Fed Staff Nowcast—was showing a wildly divergent outlook from Atlanta's. Presently, they are synced up closely: 6.0 or 6.05% for New York, too.

The following table from the same source is pretty wonky, but some might find it interesting. It shows precisely how each of the little ephemeral factoid indicators that come out most days of the last two weeks are influencing the bigger picture.

We can see that the two employment reports that I wrote about at length a week ago—from payroll processor ADP and the official (un)employment reports two days later from the Bureau of Labor Statistics—moved the first-quarter GDP outlook up far more than anything else that week. (See the "Impact" column.) That's consistent with what I wrote then: "Good Friday, indeed!" and "Taken together, we've created 1,617,000 jobs in three months, or more than double the normal rate of prosperous growth—and accelerating each recent month."

Now, for the newest week, we see six more new factoids that combined to reduce the 'nowcast' by exactly as much as it had risen during Holy Week. All of that revision of -0.13 percentage points comes from an April 7 report on exports. This is one indicator I have only rarely dissected since beginning this project in September, so I'll do so now. A reasonable and sufficient first pass at understanding the influences on and significance of news about exports and imports is this:

We export more when our major trading partners' economies are growing fast enough to demand more of our goods and services. (Yes, services are a very large portion of U.S. exports: U.S. expertise in realms like engineering, legal, consulting, and IT services, when bought by foreigners, is every bit as much of an export as an object packed into a container ship and routed through the Suez Canal. So, too, are educational services a pretty big U.S. export: every dollar of tuition paid by foreign nationals to attend U.S. universities counts. The same with tourism: spending by non-Americans at Disney World is a U.S. export.)

On the other hand, we import more when our own economy is growing fast enough to demand more goods and services from overseas, along with demanding more of our domestically produced stuff, too. Put the last two non-parenthetical sentences together, and you can see:

When the rest of the world is economically stronger than we are, our exports rise (relative to our imports); and

When we are economically stronger than the rest of the world is, our imports rise (relative to our exports).

Which of the above is true most recently? The latter. The relative weakness of our trading partners including prominently Europe (where, you've probably heard, intense virus lockdowns are being re-imposed) is reducing U.S. exports by enough to budge the GDP nowcast. Of all the possible causes of a slowing of GDP growth, I think I would prefer to have this one. Our own domestic economy can be strong, but if the same is not true in other places, it hurts our exports, and that shows up as a relatively small part of our GDP. That's the change we can see from last week to this week.

Here's another new (to me) tool that sheds lots of light on how each little factoid indicator contributes to the larger picture that I seek to provide. It comes from this U.S. Economic Calendar from MarketWatch.com, an alternative to my main way of tracking what is released when (such as the fact noted in the top paragraph that official news of GDP comes to us on April 29).

This MarketWatch calendar is great because, once a week is finished, we can see at a glance how each factoid compares to the guesspectations ("median forecast") from surveys undertaken by organizations like maybe Moody's or Bloomberg that do that sort of thing. For last week we can see that the economy outperformed expectations in six distinct ways, and fell short in only two ways, one of which comes with a massive asterisk. The one significant miss was factory orders on April 5, about which more below. The asterisk miss is April 8's jobless claims, about which I've written previously that I regard these numbers as worthless in light of the rampant fraud in the system. Some states report that the majority of claims for unemployment insurance since last year's turmoil are fraudulent. Here's what I find today doing a news search for the topic.

Repeat that search in a few days, and a different crop of headlines will appear. That's why I have stopped writing about initial or continuing claims for unemployment insurance, whether they go down (as they have been most recent weeks) or whether they go up (as they did on April 8). If there were such a thing as "factory order fraud" or "GDPNowcast fraud," I would ignore those, too.

The six 'outperform' indicators were all of the others except April 9's "Wholesale inventories." The interpretation of inventories to too fuzzy to know whether higher or lower is good news or bad. Inventories numbers includes both items sitting on store shelves that are not being sold (due to weak demand in a slow economy), and the parts and supplies on the factory floor or part way through assembly. A strong economy, with busy factories or ones that are preparing to get busy in the coming weeks, will involve increases in those types of inventories. So inventory numbers are all very ambiguous, and I ignore them.

Among the six 'outperform' indicators, I am counting the significant jump in the producer price index (PPI), even though I wouldn't count this as "good news." Although it's bad in itself, it is a consequence or by-product of [too much] good news. When strong-growing economies grow too strongly, they 'overheat' into inflation. PPI is the 'upstream' type of inflation, as opposed to 'downstream' consumer inflation measured by the CPI (coming out next week, Tuesday April 13). Goods and their parts or inputs are bought and sold multiple times in the course of production. Each transaction involves a price. Except for the last transaction when consumers buy the finished good, each earlier transaction's price is measured by the PPI. You can see that it went up 1.0% in March. That is a monthly, unannualized, rate of increase. If sustained for 12 months, it would be an annual inflation rate of about 12.7% (1.01 ^ 12 = 1.1268).

You can see that the economists contributing to the "Median Forecast" didn't see this coming. The guesspectationists are having trouble keeping up with the improving reality, as we also saw last weekend w/r/t (un)employment data. They must not be reading NO-BAH-DI-NOZ.

I've been writing about inflation pretty heavily since January, reflected in numerous surveys of consumer and business expectations and in several other ways. Now we're seeing it reflected also in the government's official statistics. This month my sources have given me some highly specific anecdotes of strong and inflationary economic activity, and I share those now:

Trucking is very tight right now too ... for a certain [product] that we get from North Carolina, they project in May there are 10 times more orders than there are delivery drivers to handle them. I spoke to a driver from Uline, a company that prides itself on getting all sorts of useful products (from 5-gallon buckets to industrial shelving, and everything in between) with next day service in various regions of the country. There aren’t nearly enough CDL drivers available to drive their big trucks, so they are hiring non-CDL drivers to drive small box trucks to do many of their deliveries now, just to keep up.

We have more trucking distribution centers going up [in my area], now with three Amazon warehouses, a new Coca-Cola center being built, and an additional gargantuan Amazon complex going in on a 160+ acre site (1/2 mile square) across from an existing Amazon center just built 2 years ago!

Plastics prices are through the roof at the moment. I’m seeing 10-30% increases across the board from one supplier of PVC and corrugated black drainage tile, and various couplers, fittings, etc., compared to last fall. [These price increases are] big enough to affect bidding, estimates, etc., where we have to use these higher prices for jobs perhaps a year away!

I noticed that this morning's "Face the Nation" on CBS opened with Mark Strassmann's report about the booming economy: job fairs with employers desperate to find workers, signing bonuses for unskilled jobs, and big pay raises for many. A few minutes later, host Margaret Brennan began her interview with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi by asking her to, as I have put it, "explain why it's necessary to pour inflationary spending fuel onto an economy that is ready to fully ignite." Pelosi's answer was completely off topic, going on about vaccines and such, as if she didn't hear or understand the question at all. Brennan did not call her on it, just moved on to her next prepared question; I was expecting no better in the way of journalistic tenacity.

Along the same track, I don't know anything about CNBC's Kelly Evans [my cable package is the skinniest possible and does not include that channel] but on Wednesday the 7th, she posted a little reflection on some recent data. Under the headline "3…2…1…Liftoff," she wrote:

I couldn't miss the strength in the ISM surveys out this past week. First the manufacturing survey—the bellwether, and one of the market's favorite gauges—jumped to a 37-year high for March. …

Then, even more impressively, the service-sector reading on Monday soared to a new record high [far surpassing the guesspectation, as we see in the MarketWatch calendar above]. … [D]oes it leave any doubt that this economy—of which 95 to 90% is in the service sector—is roaring back right now? …

Point being, the economic strength the ISM surveys are picking up is real and likely here to stay. It's not just restocking. It's not just supply-chain constraints. It's a surprisingly tight labor market out there, and if we spend anything like the $2 trillion more that's being floated in Washington right now, we might just end up skyrocketing past "normal."

… by which she means: overheating into inflation. She adds that people who last summer were "talking correctly about 'V-shaped' rebounds" were "the astute folks." As a contrast to the astute folks, she links to this guy talking about a "New Great Depression."

What about that one piece of bad news on the MarketWatch.com calendar above? About that, the same news service wrote this story, reprinted in full:

Orders for U.S. manufactured goods fell 0.8% in February, the Commerce Department said Monday. This was the first decline since the depth of the coronavirus recession last April. Orders were up 2.7% in January.

Economists were expecting a 0.6% decline in February factory orders.

Durable-goods orders fell a revised 1.2% in February, slightly weaker than the initial estimate of a 1.1% decline. Orders for nondurable goods were down 0.4% in the month.

Orders for nondefense capital goods, excluding aircraft, fell a revised 0.9% in February, down slightly from the prior estimate of a 0.8% decline.

Economists blamed the weakness in February on cold weather. The lack of key supplies may also have placed a role. The factory sector is expected to rebound quickly.

That's easily summarized as "No big deal. Weather-related. To be reversed next month."

To close, I want to focus on one other indicator from last week: "IMF increases global growth forecast, says crisis end is 'increasingly visible'." The IMF is the International Monetary Fund, the agency most famous for bailing out countries having currency crises. Periodically they put out a World Economic Outlook report featuring GDP projections for major countries, regions, and the world. On April 6 they significantly brightened their 2021 outlook for the U.S., from +5.1% to +6.4%. We have seen that two U.S. Federal Reserve nowcasts agree that the first quarter will approximate this growth pace, and the broader Federal Reserve predicts +6.5% growth for the year. Largely on the basis of strengthening activity in the U.S., Canada, and India, the IMF also revised its view of this year's global growth from +5.5% to +6.0%.

The IMF’s latest forecasts confirm that the U.S. is on track to not only return but exceed its pre-pandemic performance this year.

“Among advanced economies, the United States is expected to surpass its pre-Covid GDP level this year, while many others in the group will return to their pre-COVID levels only in 2022.”

The quotation is from IMF chief economist Gita Gopinath, saying the same thing I was saying above about imports and exports.

But wait, one other factoid on the MarketWatch.com calendar calls out for some analysis. Look at April 7. Is it possibly correct that "Consumer Credit" came in at five times the consensus guesspectation? What could that mean? Yes, these are data compiled by the Federal Reserve showing the trillions of dollars of "outstanding credit extended to individuals for household, family, and other personal expenditures, excluding loans secured by real estate." Rising indebtedness is generally interpreted as a sign of rising confidence: people borrow money when they believe conditions make it safer to do so, and more possible to pay it back. For example, consumer credit crashed in March – May last year when conditions looked grim. (The debt itself is probably not a good, wise thing in many micro cases; but the aggregate willingness to undertake it is a good thing in the macro view.)

Well, it's true that February consumer credit grew by $27.6 billion, which was quintuple the expectation and better than the estimate of any individual forecaster. The total amount of outstanding credit was 7.9% higher than one year earlier; by contrast the January total was equal to January 2020.

The Bloomberg.com story, "U.S. Consumer Credit Surges by the Most Since Late 2017," concludes:

The overall improvement in borrowing highlights a consumer that is growing more confident as the economy accelerates, job growth picks up and more states lift burdensome restrictions.