Employment, the Economy At Large, and Many Signs of Inflation Are Growing Quickly

So why are we creating trillions of "free money" to give to 85% of households?

The big news of the week in macroeconomic data, as always in weeks containing the first Friday of a month, was surely Friday's official report of March employment growth and the unemployment rate. Good Friday, indeed! I figure everyone has heard the headline numbers: a net +916,000 new jobs, and the unemployment rate down 2 ticks to 6.0%. In times of normal prosperity, we often achieve net job gains in the +200Ks. Up in the +300Ks can happen, mixed with some months in the +100Ks. So, March saw about 4 normal months' worth of job gains, or 3 really good months' worth. You might recall that my newsletter of March 8 highlighted the previous month's jobs report this way (emphasis added at the end):

"U.S. added 379,000 jobs in February, vs 210,000 estimate." The pull-quote from the text seems to me to be this:

“Today’s jobs report sets an extremely positive tone as we move into warmer months and the pace of COVID-19 vaccinations accelerates,” said Tony Bedikian, head of global markets at Citizens Bank. “While the labor market still has a lot of ground to make up, we are in a different place than we were a year ago and the economy seems poised for a strong rebound.”

One factor making matters even better than the numbers appear to be is this: The net +379,000 jobs would have been 61,000 higher than that, but for a loss of that many construction jobs. Those are surely due to the crazy snowstorms of February, which were unseasonable in many of the places hardest hit. So the March employment report will show all of those jobs coming back, plus whatever net new construction job growth occurs, plus a great many COVID re-opening jobs in other sectors. March is going to be huge, is what I'm saying.

Despite that easy call on my part, the professional guesspectation-makers didn't dare to go nearly high enough. CNBC's main story on the numbers was headlined, "Jobs report blows past expectations as payrolls boom by 916,000 in March." The number cited as economists' guesspectation was +675K. The fine print in the story gets even better:

In addition to the powerful gains for March, previous months also were revised considerably higher. The January total increased 67,000 to 233,000, while February’s revisions brought the total up by 89,000 to 468,000.

Taken together, we've created 1,617,000 jobs in three months, or more than double the normal rate of prosperous growth—and accelerating each recent month. I emphasize again that these are net new jobs, taking account of the gains and losses across the economy.

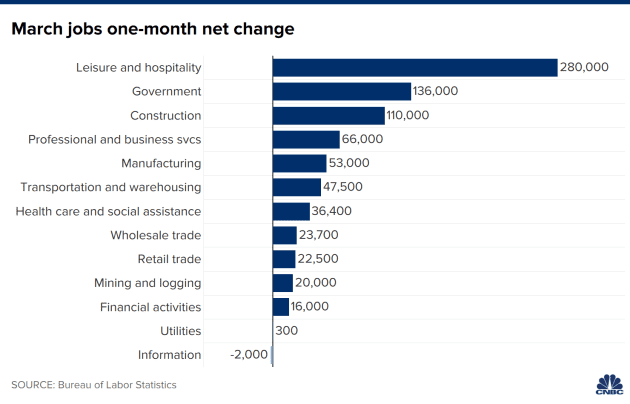

What about my prediction a month ago of "a great many COVID re-opening jobs" to be created outside the construction sector in March? Consider this chart, courtesy of CNBC's graphics department:

I think this is easy to interpret: Construction did make up for Feb's weather-induced setback, and then some, exactly as predicted. The outsized gains were in Leisure and hospitality, the sector that was slammed most—and whose recovery has lagged most—due to COVID. 'Professional and business services' is a rather amorphous group that includes a lot of office jobs also impacted by the pandemic, and now coming back. The other sectors mostly showed gains in line with healthy economic conditions.

Regular readers know that a couple days before the official Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) report that we've been talking about, the payroll-processing firm ADP releases its own data about how many workers are employed by the business who are their customers (and then extrapolated as best they can to the whole private-sector economy). ADP's numbers have been running below the ones from BLS that generate the splashiest headlines. In part that's because ADP doesn't attempt to guess what hiring is being done at government agencies, so BLS's +136K jobs in Government for March are missing from ADP's total.

Still, it's indicative of something good that ADP found +517K jobs in their Mar 31 press release – the best since September. (ADP also prepares this infographic .pdf view.) The sector detail tracks the story from BLS more closely this month than usual: Leisure and hospitality showed a disproportionate comeback, most other sectors did well in a more proportionate way, and the Information sector saw a negligible loss of jobs. I take that last fact to merely reflect that this sector has been booming, and a random monthly variation occurred.

If you can stand one more link to and quotation from a CNBC story, here is another from April 1 giving a little broader perspective about what the recent numbers imply for broader economic health, as measured by Gross Domestic Product.

The median growth forecast for second quarter GDP is now 9.3%, according to the CNBC/Moody’s Analytics Rapid Update of economists’ forecasts.

“The consumer is the big story. It’s not just the stimulus bills. ... It’s the leftover stimulus money that’s accumulated in bank accounts,” said Ethan Harris, head of global economic research at Bank of America.

Beyond the week's employment reports, I want to quote at length some news from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas concerning economic activity in the district that includes all of Texas and parts of Louisiana and New Mexico. I do so not to prioritize one region of the country, but for two reasons. First, the Dallas Fed is the most recent district to conduct release such surveys, but is not an outlier in what information it uncovers. The article notes that "Other regional banks in the Fed system also have reported strong improvement in manufacturing and services"; links to those reports from New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Richmond can be found in this calendar. Second, the Dallas district is unique in providing a convenient and comprehensive matching pair of manufacturing and service surveys, as you see in the first two paragraphs below. Farther below, in the bottom half of the excerpt, the newspaper's attention turns to some of last week's national indicators, saving me the trouble of summarizing and linking the Conference Board's Consumer Confidence Survey and the Institute for Supply Managers' manufacturing index. (Here are two complementary stories from Thursday April 1 about the latter.)

At last, here's the excerpt from The Dallas Morning News, complete with links (emphasis added):

In a March survey by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Texas manufacturing executives reported big gains in output, new orders and shipments. On two key metrics — production and capacity utilization — the Dallas Fed index readings were the highest in the survey’s 17-year history.

The Texas service sector also reported stellar improvement in March. Revenue gainers outnumbered losers by over 2-to-1, a giant leap from February and well ahead of historical trends. Service companies also had gains in employment, hours worked and capital spending.

On two metrics, general business activity and company outlook, executives reported the highest monthly marks since the Dallas Fed’s service sector survey began in 2007. Those with improved business activity outnumbered the decliners by nearly 5-to-1.

“We are running at near capacity,” an unnamed machine manufacturing executive told the Dallas Fed. “Business has never been better.”

Said an executive in administrative and support services: “Inactive clients have begun to reach out and reconnect to discuss future hiring plans.”

A maker of computers and electronic products said demand continues to strengthen broadly, lead times are being stretched and many peer companies are raising prices: “I have not seen this dynamic in my 30-plus years in the industry,” the executive told the Dallas Fed.

…

The upbeat reports are not limited to Texas. Nationwide, manufacturers expanded in March at the fastest pace in 37 years, according to a closely watched index from the Institute for Supply Management. Other regional banks in the Fed system also have reported strong improvement in manufacturing and services, said Emily Kerr, a senior business economist at the Dallas Fed.

“There’s just widespread strength, both in measurable activities like production and in expectations and company outlooks,” Kerr said. “There are certainly a lot of reasons to be optimistic about the path forward.”

COVID-19 vaccination rates are climbing fast, and some states, including Texas, have relaxed restrictions on businesses. Financial help has continued to flow from Washington, including $1,400 checks to individuals, unemployment insurance supplements and loans for small businesses.

Consumers are turning more optimistic, too. The Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Survey jumped over 19 points in March to its highest level since the pandemic started.

…

Many executives are already complaining about the difficulty of finding new hires, and they often blame federal relief programs.

“We are in desperate need of employees,” an administrative services executive told the Dallas Fed. “If the government is going to pay people to stay at home, they will stay at home.”

That’s not what bothers Andy Ellard, co-owner and general manager of Manda Machine Co. His Dallas firm makes machine parts for aerospace companies and defense contractors, and he says it’s getting tougher to line up raw materials such as steel and aluminum.

Prices are rising and inventories are falling, continuing the supply chain problems that have disrupted manufacturers throughout the pandemic.

While looking for something else, I happened to find this:

https://www.creighton.edu/economicoutlook/midamericaneconomy/

Creighton is the regionally prominent university in Omaha that might not be so well known to people far from the heartland, and the Mid-America region that they track comprises the 9 states in the two stacks atop Texas and Louisiana: Oklahoma to North Dakota and Arkansas to Minnesota.

March survey highlights:

Creighton’s regional Business Conditions Index climbed into a range indicating very strong growth.

The speed of the delivery of raw materials and supplies slowed to its lowest pace on record.

The wholesale inflation gauge indicates substantial upward price pressure.

More than eight of 10 supply managers reported supply bottlenecks and delays for February and March.

More than one in four manufacturers named shipping and transportation delays as a top factor producing supply bottlenecks.

Since bottoming in April of last year, the region has added almost 46,000 manufacturing jobs.

…

Other comments from March survey participants:

“My firm is experiencing steel shortages, plastics and resin shortages, components from overseas supplier shortages.”

“We are seeing supply delays for all issues listed.”

“It is not just Covid causing the shortages. Issues: 1) Hurricanes last fall disrupting supply; 2). The Winter storm disrupting supply; 3). Industrial buyers panicking and hoarding.”

“The Biden (Harris) administration’s fiscal actions will continue to pressure inflation, drive up unemployment, and lower consumer confidence. The crash is around the corner.”

Wholesale Prices: The wholesale inflation gauge for the month dipped slightly to 94.0 from February’s record high 95.2.

As reported by a supply manager, “I purchase a lot of steel components and the increases are ridiculous. Steel availability is tight. I see hyperinflation coming.”

“At the wholesale level, Creighton’s survey is tracking higher and higher inflationary pressures. Metal products and lumber, for example, are experiencing significant upward pressures in prices. Since June of last year, metal prices have expanded by 14% and lumber products have advanced by 22% according to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data. Despite rapidly expanding inflationary pressures at the wholesale level, the Federal Reserve remains committed to its current expansionary policy,” said Goss.

Confidence: Looking ahead six months, economic optimism, as captured by the March Business Confidence Index, climbed to a solid 58.0 from February’s 50.0.

“Despite supply bottlenecks and rapidly rising prices, the expanding U.S. economy pushed economic confidence among manufacturing supply managers higher for the month,” said Goss.

The as yet unstated implication of much of all this reporting is really the primary running theme that has emerged in these newsletters since early winter or arguably since the first one in September: the U.S. economy is recovering well; it's tracking the recovery from the virus; and therefore as the vaccines gain the full upper hand, the economy will regain full strength.

The further implication is that the last round of American Rescue Plan stimulus, signed into law on March 11, and the subsequent two rounds of multi-trillion dollar spending bills now under discussion are completely over the top. Just as the economy is on its way to returning to full speed, our fiscal policy is hitting the accelerator even more. Or, to mix the metaphor again, I'll restate what I wrote three weeks ago about watching a Biden economist on TV "struggling to explain why it's necessary to pour inflationary spending fuel onto an economy that is ready to fully ignite."

Now we see further evidence in the Creighton survey of "rapidly expanding inflationary pressures" and, when you go back and look at it, the same in each other piece of information given here this week, and last week, and the time before that, and… .

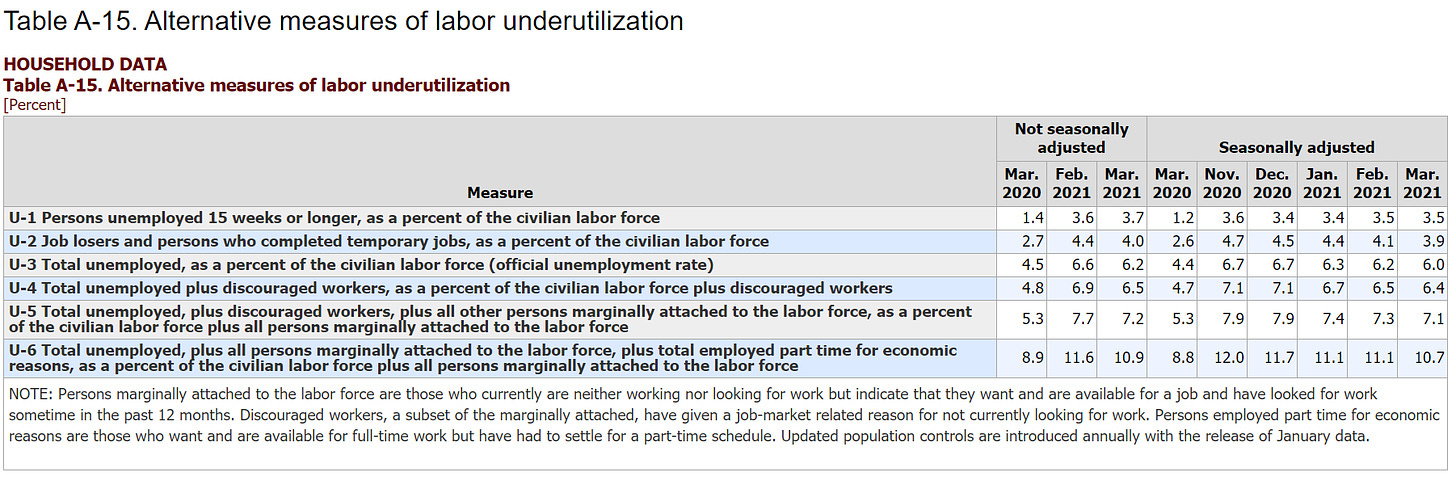

The poverty rate was pushed up during the pandemic to 11.8%; the unemployment rate is—take your pick—6.0% or up to 10.7% when you include those who aren't officially counted but might be thus counted under the broadest definition the BLS calls U-6 [see table below, and notice that U-6 has been falling twice as fast as the regular 'U-3' unemployment rate has been];

… various estimates of those who are housing-insecure or food-insecure are, I believe, in a similar range. A careful reading of the notorious Federal Reserve survey that generates the wildly mis-reported and demagogued "40% can't afford a $400 expense" shows that the true number is about 14%. And that percentage has been falling every year since it began to be measured early last decade—including a decrease between 2019 and 2020. (It might be next month when the Fed updates this survey; if so, I'll be sure to read it carefully and report on it here.)

Of course, these categories consist, almost entirely, of the same people; it's not that you can add 12% poor + a different 10% unemployed + a different x% at risk of eviction + other groups to yield an At Risk population of 40 or 60 or 80% of the population. Even if we add a few more percentage points to the At Risk group just to be safe, it still raises a very good question that I can't believe I've never heard formulated anywhere else:

Why in the world did we send newly-printed "free" money to 85% of all households?

That's about 70 percentage points (or at least 65) more than who really needed the money.

The signs of inflation we can see everywhere are all very predictable. As if the supply-chain shortages cited by several Creighton survey respondents is not leading to enough cost-push inflation, and as if the economy recovering at double or triple its typical growth rate is not enough pressure on the demand-pull side, we have a government that creates vast amounts of money out of nothing to further fuel demand-pull inflation. The middle and upper-middle classes having received piles of "free" money explains why so much of it is sloshing around the speculative cryptocurrency markets, being played with by amateurs on Robin Hood, jacking up the prices of second homes and everything else, and generally being poured as "inflationary spending fuel onto an economy that is ready to fully ignite."

But remember what NPR's Weekend Edition thought was the ONE thing you needed to know in their first sentence of the Sunday broadcast four weeks ago:

There is ONE thing you CAN say about the massive coronavirus bill that passed in the Senate yesterday: It is aimed SQUARELY at millions of broke and anxious Americans.

Help for the 15% or so aimed squarely at the 85%. Enjoy it while it lasts.